By Dr. Moazzam Khan Durrani

Every year when the sorrowful days of Muharram dawn, my mind journeys into the past. Not only towards the universal grief of Imam Hussain (AS) and the tragedy of Karbala, but particularly towards the dusty lanes of Ahmed Pur East, the shade of the ancient Bohar (Imambargah), and the old walls of Kattra Ahmed Khan. Here lie the roots of my grandfather, where my family’s story is intertwined with the profound and tolerant culture of Ashura that once flourished in the heart of the Wasaib (Saraiki Region).

When my grandfather, Ahmed Nawaz Khan, settled in Ahmed Pur East due to his job, his house was very close to the Bohar Imambargah (famous for its ancient Banyan or Fig tree). The histories narrated by my father, his contemporaries, and my grandfather’s peers paint a picture of a society utterly different from the fragmented tales one hears today. Tolerance wasn’t merely a word; especially concerning the sanctity of Muharram, it was the blood coursing through their veins.

The elders speak of a time when sectarian labels would blur, particularly in matters of worship. Members of the respected Syed family of the area recount how my grandfather served them not just out of responsibility, but from a deep moral duty (Farz-e-Imani). Food prepared in my grandfather’s house was sent daily to the homes of the Syeds, without a thought to whether they were Shia or Sunni. This was not charity; it was honor. Remarkably, the food sent for the Syeds took priority; only after its distribution would the children in my grandfather’s own house eat. This was their steadfast routine, a testament to the ingrained respect for the Ahl-e-Bait (AS) in their daily lives.

The observance of Ashura was described with an intensity that touches the heart. It was not a spectacle; it was a deep, shared mourning. “It was as if a death had occurred in every home during those days,” my father would recount. The grief for the household of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) was palpable everywhere, personal and societal alike. A solemn atmosphere prevailed.

When my grandfather retired, he moved not to his ancestral city of Bahawalpur, but to his maternal city of Rahim Yar Khan, settling again near Takia Lal Faqir, adjacent to another Imambargah. Here too, the remarkable spirit of tolerance manifested uniquely. The same piece of land that served as a Sunni Funeral ground (Janzah Gah) all year would transform into a sacred Imambargah space for the ten days of Muharram. This unhesitating sharing of sacred space bore witness to mutual respect and understanding.

My family’s devotion was deeply personal. My maternal uncle, Muhammad Khan Durrani, the only son born after five daughters, fulfilled my grandmother’s vow. Every Ashura, he would become Faqir-e-Hussain (Hussain’s Mendicant), and then the Niaz-e-Hussain (food offering for Hussain) would be presented to people with reverence. This tradition was repeated for me. As the only son born after three sisters, my paternal aunt vowed on my birth to offer a dupatta (veil) to Syeda Zainab (SA) during the Ashura procession. Even more touching was the vow of another of my father’s aunts. She desired that my first cloth be an utran (worn garment) of a Syed. She contacted the custodian (Mutawalli) of Darbar Maa’u Mubarak, a friend and neighbour of my uncle. Understanding the sacred nature of her vow, the Syed respectfully gave his old kurta (shirt) for this purpose.

My grandmother and maternal grandmother (Nani Amma) participated fervently in the mourning rituals. They provided food (Langar) and water (Sabeel) during Muharram. I recall childhood memories myself: serving water to mourners outside the Takia lal Faqir in the scorching sun during the procession. Respecting the sanctity of these days was paramount in our homes. TVs and radios were switched off and locked away in cupboards for ten days. Even children’s laughter was strictly restrained. Reprimands were effective and instructive: “What face will you show the Prophet (PBUH) on the Day of Judgement when members of his household were mercilessly martyred, his women disrespected, and you are laughing and playing during these very days? Feel the grief, share the pain.”

But this tapestry of shared grief and deep tolerance began to unravel abruptly with the next generation. A smog of suspicion and hate speech clouded the air. Tragically, leaders bridging sectarian lines began to be targeted and killed. Ashura processions, once expressions of shared sorrow, now emerged under heavy security, symbols of fear replacing trust. Even within families, elders who once upheld traditions began to abandon them. Offering food and water started to be seen by some as “promoting Ashura culture,” a ghastly deviation from the past’s inclusive reverence. Shared spaces became tense; the spirit of openness felt lost.

Yet, traditions rooted in genuine love and respect possess remarkable resilience. Today, whispers of the old tolerance are rising again. Deliberate efforts at bridge-building are underway. Sunnis are once again seen offering water (Sabeel) and food (Langar, Haleem) during Ashura. Sunnis attend Majalis (mourning assemblies), receiving the message of Hussain (AS). Most significantly, the shared space at Takia Lal Faqir functions without hindrance as both a Funeral Prayer ground and an Imambargah, echoing the practical harmony of the past. The Bohar Imambargah, perhaps less accessible before, is now open year-round to people of all sects. People mourn the Ahl-e-Bait (AS) with open hearts. The distribution of Haleem on Ashura day is a powerful symbol of shared giving and remembrance.

Most notably, people from all sects participate in the Ashura processions. Virulent hate speech has decreased markedly, and the targeted killings of leaders crossing sectarian lines have stopped. While vigilance remains essential, society feels like it’s moving towards a renewed level of tolerance, a place where mutual coexistence is not merely a dream, but a living reality once again.

This reminds us that the spirit of Hussain (AS) transcends sect. His message of revolution for truth, establishment of justice, and practical demonstration of mercy is universal. The tolerance of our elders was not weakness; it was a deep strength rooted in the true spirit of faith. Seeing the initial signs of this spirit returning gives me a ray of hope. Mourning Hussain (AS) together can serve as a bridge, uniting us in our shared humanity and reverence for the sacred.

Dr. Moazzam Khan Durrani is an academician in the Department of Anthropology at Islamia University of Bahawalpur. He played a pivotal role in renovating Noor Mahal Museum and collaborates with the University of Cambridge’s MAHSA Project to Mapping and contextualize history through a modern lens.

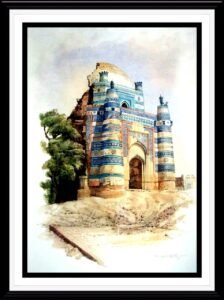

Figure 1 Picture Bibi Jiwandi Painted By Ghulam hussain

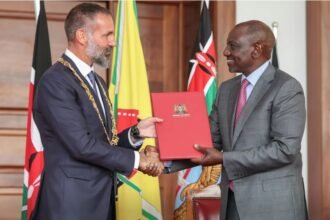

Figure 2 Taqia lal faqir Funeral Prayer Area rahim yar Khan

Figure 3 Taqia Lal Faqir Rahim yar Khan

Figure 4 Bohar Imam Bargah Ahmedpur East